This work revolves around the critique that the current way of building does not accomodate the multiple social, professional and psychological changes in peoples' lives today.

The text Transformation House I was submitted for an architectural competition to design an alternative dwelling for the new city of Leidsche Rijn in the Netherlands, organized by Bureau Beyond. For the second round of the competition the animation film was made – not as a final design, but to visualize the concept of a structure expanding and shrinking as a consequence of the development of an individual life.

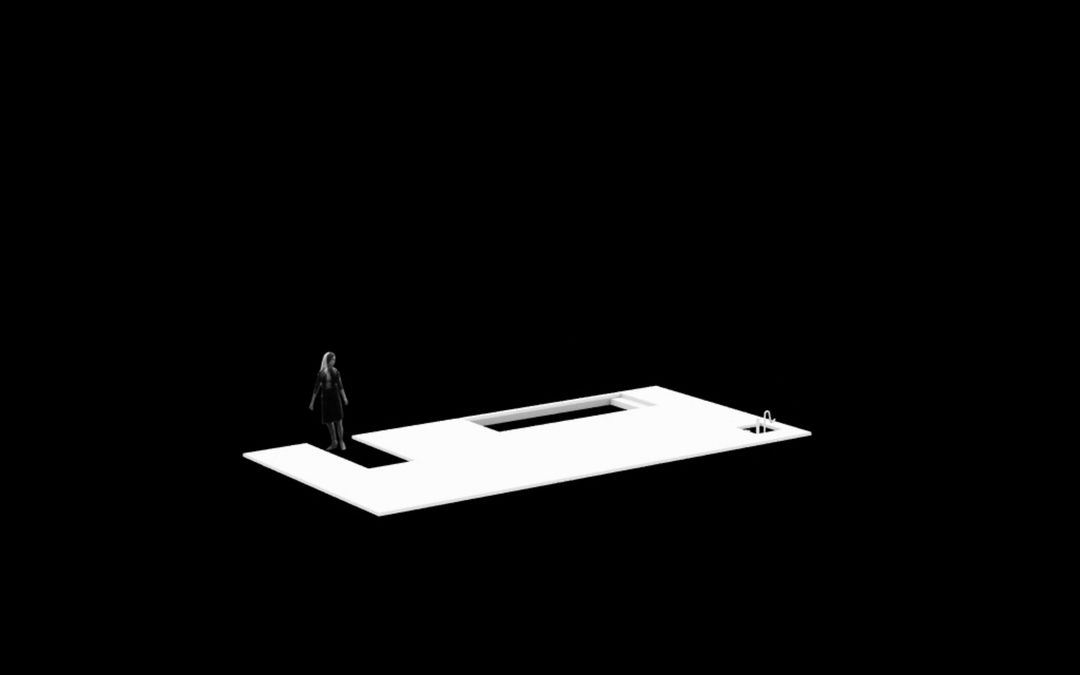

Transformation House II, still

Animation made in collaboration with Olivier Campagne at Artefactory, Paris, F.

Exhibited

VIP Huis Competition finals, Het Gebouw, Leidsche Rijn/ Maak ons Land, Nai, Rotterdam / Space for your Future, MOT, Tokyo, Japan / How to live together, 27th Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil /

Transformation House II, still

Transformation House II, still

Transformation House II, film

PART I

A house is not a hiding place.

The place where we will live, is no longer the self-imposed jail it has been for the past two-thousand years. From this moment on, the house as we know it will change programme, because people have changed, or at least the lives of people have changed.

Most of human evolution took place before the advent of agriculture when men lived in small groups, on a face-to-face basis. As a result human biology has evolved to an adaptive mechanism to conditions that have largely ceased to exist. Despite the fact that the brain capacity of man has not notably expanded since the stone age, the social and professional demands of today call for a radical reconsideration of the way we view our habitat.

The conditions we live in appear to be choices, but in fact they depend largely on availability, coincidence, and most of all, on pure luck.

The house will cease to be a shelter from the elements. The notion of a retreat for the vulnerable unhairy species is obsolete. Issues like nourishment, as in: being able to collect enough food to stay alive, or the imminent danger to become food for others yourself, are negligible concerns in this part of the world. The same applies to climatological factors. The primitive reflex to design dwellings to shut the elements out, is hard to delete from our system, since we despise the weather in our country so much that to ignore it seems to be the best defense.

Another point of interest for the two-legged mammal is possession: how to obtain it, how to multiply it, and most of all how not to lose it.

This led to the false conclusion that a house is a storage place for goods. The need to lock away collected commodities is an endless one. Large groups of people lose their reasoning and move to virtual wastelands, led by the promise of more storage ability.

Single objects are often interchangeable and can be made of recycled material. Emotional attachment from now on, exists only from one living creature to the other – plants included. Please note that the stucture at stake here, is considered to become one of these living creatures.

It seems that the design of houses has been largely driven by negative factors.

Now that all practicalities of living in the 20th century have evaporated into mere theory, former concerns on human housing from the year zero to the year two thousand can soon be looked up in history books.

PART II

A House is not a home

My parents met in the early sixties, when they were studying architectural engineering in Delft.

I am born in 1966, my sister a year earlier. We lived on the highest level of a four-floor flat on the outskirts of Haarlem. My father went to work, my mother stayed at home with two babies. With little else to do, she wondered why so many people like herself, were sitting alone in a box stacked on top of another box all day. This depressed the hell out of her. A few years later the four of us moved to Amsterdam, where we had two boxes on top of each other. But my mother remained depressed. She decided to leave the family in 1977, to live elsewhere and study architecture. Her ideal was something called “Central Living”, a form of co-habitation that she promoted in articles and as part of a support group. The idea of Central Living is that a group of people choose to share a building and its facilities, and sometimes share other, more personal things as well. Meanwhile, she lived alone in a small room she rented. When she finally managed to sublet a more spacious apartment, my sister moved in with her.

My father just seemed to work or sleep. One day he came home and announced that he was going to live with a woman he described as ‘pearl’, who stayed on a houseboat in one of the canals of Amsterdam. He took a bag of clothes and some books and went off.

Now that my parents had left home, I remained in the two-storey apartment, surrounded by the brown and orange furbishing they’d picked according to the fashion a decade earlier. Despite the admiring remarks of my friends about my huge flat, I was relieved to find a student room in the city centre.

My father, then over 50, started a new family with ‘pearl’. My mother had a Living Apart Together relationship with a law student 15 years her junior.

(continued)

PART III

Indefinite walls for indefinite futures

The growing variations in professional and personal activities during a persons’ life today are poorly reflected in the way houses are designed and built.

Change and time are rarely considered useful factors in building plans; it seems to contradict planning as we know it.

The proposal for this structure in Leidsche Rijn revolves around the idea that the location where someone works, sleeps and interacts can be a stable factor in a life marked by transformations, without the structure being the dumb and deaf entity it is today.

Transformation House is leading in the direction of a modular set of connectable forms in different sizes, shapes and materials, from which the owner can assemble a bungalow or villa to fit momentary needs, and add and subtract according to any changes in his/her personal or professional situation.

The word modular points to the system as developed by Le Corbusier. This once ideal system will be adjusted to meet the needs of contemporary and future men and women. Apart from the obvious physical changes, like the increase in average size of man, psychological factors become an important part of the equasion as well. The fact that the senses are hard to measure does not mean they’re not important.

This proposal takes the advantages of the conventional ‘box’ by allowing private spaces (exit loft-architecture), but eradicates the claustrophobic effects of the fixed scale and rigid proportions, the one we locked ourselves up in, in order to escape the threatening world outside.

This permanently unfinished house can have a radically different appearance, according to the elements used. Included are elements that allow the spaces to be placed at different heights by using poles, or can be placed on wheels for easy re-location on the premises itself.

Possibilities for radical and almost instant transformations in the interior, such as walls sliding and rotating in every direction, are to be further developed within this system.

PART IV

A house is not a museum

Imagine living in a world where the Rietveld-Schöder house had not turned into a museum. Imagine that the ideals as articulated in that house had rooted themselves into the considerations of mainstream architects and builders, and a large amount of people had embraced the idea of living in a space that allowed for a series of transformations.

(letter to Gerrit Rietveld)

May 29th, 2006

Dear Gerrit,

A few weeks ago, my father quit his job at the Rietveld-Schröder House. Having worked as an engineer for the National Building Society all his life, he considered the house you’ve designed for and with Truus Schröder-Schräder an appropriate environment for a post-career volunteer job, where he could make use of his love for architecture and design, guiding groups of tourists around the house.

He explained his resignation by giving just one reason. He said that the ride to Utrecht from his home in Almere, is too long if it is merely made to tell the same story every time.

My father did however, enjoy the questions of the visitors, he told me. He’s kept a record of the ones he could not answer, to look for the information later, at a moment when the visitors themselves were already on their way back to Tokyo, or busy seeing another important European sight.

In most of the literature about the Rietveld-Schröder house, as romanticized as that may sometimes be, your relationship to Mrs. Schröder is described in technical terms.

It’s probably unprofessional to consider personal circumstances when reviewing a designers’ work. But isn’t the Rietveld- Schröder house the ultimate metaphor of the radical changes in your personal life at the time? The idea of transformation is expressed most clearly in the changeable structure inside; rooms can change size and shape, appear and disappear according to their function and the needs of the inhabitant at any moment of the day or night. It’s tempting to think of the ‘hidden’ storage places in terms of psychological as well as practical signs.

The big changes you’ve made in your personal life may have been quite a scandal at the time.

Here, in the 21st century, it’s common practice that people change habits, houses, jobs, spouses, age, offspring, language, looks, foods and timezones within days, hours, sometimes minutes.

What remains a mystery to me is why a lot of the ideas as formulated in the Rietveld-Schröder house – so clearly ahead of their time – have become relics; things to be visited and looked at in retrospective admiration, instead of having naturally developed into general parameters for building in the 20th century.

The paradox of the time I am writing you from, is that one is expected to have conflicting personalities; on the one hand be a stable and decisive person, and at the same time being able to adapt to an infinite range of social and professional situations.

The form of living for a person under these demands, is to be further developed, starting from your heritage that, unjustly so, has remained unique.

Yours truly,

Barbara Visser

PART V

Why choose for this plan?

One of the qualities of this idea is that it would never work as a museum. Transformation House only has meaning when its form is not fixed in time.

If the now still invisible neighbours were to be part of the system, a number of variations could be on display at the same time.

Another good reason to realize this project is that it’s a contrasting view to the surrounding city of Leidsche Rijn, without diminishing the reasonable and pragmatic nature of this city.

I believe that variation in building programmes will result in a greater variety of inhabitants in Leidsche Rijn, which is ultimately what a city needs to be functioning apart from the artificial programming that is omnipresent as it is.

Transformation House is a proposal for a way of building that is more related to the reality of peoples’ lives today, and is based on my own experiences in the past and present. It’s my great hope that this idea of structure is not bound to be an artefact to be guided through in 2086, but one example of an idea, which by then has become an intrinsic part of the way homes are designed and built.

May 29th, 2006